Trust - that old-fashioned value

I'm an avid ATP follower, and an article highlighted the value of 'trust'. When I was a child, the word was in and out of my head frequently, simply because my mother used it a lot. It ranged from simple propogandist sayings like, 'never trust someone with brown eyes', (which I'm sure had been transmitted from her own mother), to more basic observations about being able to rely on each other as friends.

Reliability

What of course she was really meaning was that people should be reliable and loyal. If they fulfil this, then these are people you can trust. So, through my childhood, I have been very conscious of finding people who are reliable and with whom you can trade loyalty, and you can then trust these people, just as you would trust yourself. My observation though, is that there aren't that many people we can trust, that making our acquaintances go through tests to prove their loyalty and reliability can be a long and trying procedure, and there are some people, maybe some particular types of people (ones with brown eyes!) who we'll never trust, however hard they try.

Ask

The ATP article reported on the final pro match of a Roland Garros champion, Juan-Carlos Ferrero. Like all champions of clay, he built his success around an immaculate defensive game, the ability to get the ball back in play over long periods. He was not a shot-maker, he cannot be categorised into anything that might be called a crowd-pleaser. He was smooth enough, without having any strokes or traits that made you sit up and wow at him. And why should he? He was a fantastic tennis player, who had a remarkable career where he achieved everything he should have achieved, and a bit more too. He could be categorised as an over-achiever, because many more cultivated, exciting and aesthetic players haven't achieved 5% of what he achieved.

The surface

I have to confess that my favourite surface is clay. You feel that you are playing on the most testing surface of all, but it is also forgiving. It is good on your body, and good on your mind. Whilst it gives you enormous physical tests, it is slow enough to give you time to think, to play with the ball, to play the game of tennis patience, and not just think about making winning shots all the time.

Clay was the last surface I learned to play on, and it took me a few years to transform my fast, frantic, shot-making game into one of vision, control, endurance and variation that you must have to be successful on it. And it is these qualities that Ferrero probably learned FIRST, and he, as far as I can tell, never really learned the frantic, shot-making game, because he didn't need to.

The clay season is so important on the ATP calendar, he was able to revolve his career around a good 20 weeks of clay court tennis per year, and if he ventured onto other surfaces, like grass, or indoors, he suffered from no illusions. He knew his game wouldn't transcribe well, and he didn't really try. It doesn't mean to say he didn't play good matches off clay, but they were very much fringe performances, things that filled out his professional life, but not those that gave it his chief substance.

Expertise

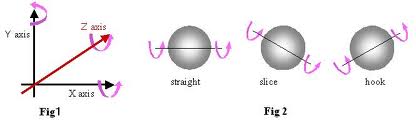

One feature of Ferrero, is that he was nevertheless atypical. Many of the Spanish clay courters are big spinners of the ball, mostly topspin, but also slice, and kick serves to get the ball into play. Ferrero was not a huge spinner of the ball, despite his extreme Western forehand grip. He didn't create wide circles on the ball, with a big physical effort swing to accentuate this spin. No, his racket shapes were more simple, certainly less tiring on him, and made his game easier to manage. This should have made him less prone to injury, as many physical players are. But in fact he had serious wrist and knee injuries at a peaking point in his career, that may have cost him a couple of big titles.

So his method fitted his body, and he was clearly ambitious and well-organised without wanting to adopt any star status. Whenever celebrating any match victory, indeed Roland Garros itself, there is no extravagant jubilation, just a simple satisfied smile of a job well done. He didn't play the gladiator in victory, didn't pick unnecessary mental battles with his peers, he just did his own thing, and let everyone under-estimate his rather delicate-looking game.

Those tennis knees

In the ATP article they mention, as I have, his mother. His mother was probably one like mine, a mother who insisted on being true to yourself, defend your qualities at all moments of your career, and stick with those people who are your entourage, your tried and trusted supporters. His mother would have had a horror of him becoming a big-head, or foul-mouthed, or a racket-thrower. As it turned out, Ferrero's mother died when he was still only 17 at a Tennis Academy. There is a suggestion that maybe losing his mother so early imprinted all the more strongly her ethics on how the rest of his career panned out.

Support

Ferrero was a successful junior, a more frequent feature of clay courters than his shot-making colleagues of other surfaces. What he brought to the pro game, was a highly-polished junior game - great retrieving, great anticipation and desire to run all day.The junior boys game is not about great shots, and physique, it's a bit "girlie", a game of ping - pong to see who'll make the first mistake. Ferrero had a junior game, on a pro court. He was not the only exponent of this type of game, but I can think of few who were better at it. The key was that he had complete trust in his basic set up, his method, and that trust emanated into his entourage. I think he was very easy to manage.

Sharpen your bite

He had an interesting nickname too - Mosquito. I wonder whether it was his pro colleagues who called him this, or maybe even a nickname that had stuck from school. He was somehow a bit fragile, a bit slight, but had, like a mosquito, great change of direction, and a flitting, fizzing, aspect that kept putting him in the right place, at the right time. He was mostly a step ahead of his opponents. His movements was too quick, too early and too precise.

Spinning ball

But surely he did play great shots? The Ferrero great shot was almost always the same. He'd be fizzing around at the back of the court, the forehands and backhands sizzling rather than cracking off his racket. He would maintain tempo, never let it get too slow and loopy, in fact I don't think he could hit like that. But he also didn't force the ball either. He didn't go looking for a great shot, and then whoosh, a great long line winner from the back of the court! His winning shots came when you weren't ready for it.

Through his slightly quick tempo and ability to get into position fast, he'd find himself early on a ball, earlier than his opponent, and his 'normal' shot would become a great winner. And Ferrero would play lots of these 'great shots', but I'm sure he wasn't looking for them. They just came quite naturally out of his normal tempo. His edge on speed would catch his opponent sleeping by milliseconds, and the shot was through him. And you could tell that Ferrero wasn't searching for winning shots, because he never had to celebrate them. They came naturally, as naturally as his 'non-winning" shots earlier in the rally.

Similarly, his serve. His was never a power shot, just a simple slice that fizzed nicely off his racket. And then, whoosh, an ace! From Ferrero, an ace? Yes, he did hit aces, or at least, many unreturnable serves, because that fizzing slice lulled opponents into a false sense of security. The simplicity of the shot disguised great control, and in particular great accuracy and control of speed. Just by flicking the ball a touch at contact, he'd be able to hit winning serves by surprising his opponent, but giving the ball that extra touch.

Too high

It seems Ferrero was a ground-breaker in his own country, a Davis Cup stalwart, a model for others to copy. You can tell he was a man who carried his youth around with him - his playing style, his traditional family and people values. A man to trust definitely.